H. Beam Piper: The Last Cavalier

"For all his knowledge, Beam was no dry intellectual. He was a storyteller; a man who could keep you up all night with his books and his tales. He had respect for the intellect and for intellectuals, but he was never one of the breed. He was a cavalier."

Jerry Pournelle

"Federation"

On the weekend of November 6th, 1964, H. Beam Piper shut off the utilities in his apartment at 330 East Third Street in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, placed painter's drop cloths over the walls and floor and shot himself with a .38-caliber pistol. Marvin N. Katz, a reporter for Grit Publishing, wrote in the Analog Science Fiction letter column that there was a suicide note, but it did not give any reasons for the fatal decision. In a typically Piperesque comment, he did state: "I don't like to leave messes when I go away, but if I could have cleaned up any of this mess, I wouldn't be going away. H. Beam Piper."

Any time an important artist or writer's work is brought to a premature end by death, those who love his work suffer the greatest loss of all. H. Beam Piper's needless death is one of the true tragedies of science fiction. Not that the field has been immune to tragedy: Stanley G. Weinbaum, who died at age thirty-six after a sudden and meteoric rise, and Cyril Kornbluth, whose prodigious talents were brought to an end by a heart attack at age thirty-five, are two that come instantly to mind. But tragic as these unexpected deaths were, they lack the tragic irony of Piper's suicide, brought about by his mistaken belief that his career as a writer was over, only a few years before the SF boom of the 1960s and 1970s would transform science fiction into a cultural icon and in another decade make millionaires out of its top practitioners.

H. Beam Piper, who was writing at the top of his form at the time of his death, had quickly, and without the usual hype and fanfare, established himself as one of the science fiction fields' finest authors. In the five years before his death, Piper had made the turn from promising short story writer to major novelist, with novels such as "Four-Day Planet," "Cosmic Computer," "Space Viking," "Little Fuzzy," "The Other Human Race" and his final work, "Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen." Jerry Pournelle believes that Piper would have soon been ranked among the top echelon of SF writers, right up with Heinlein, Clarke, Asimov and Bradbury, as well as sharing their financial success along with their growing literary reputations. As Lester del Rey noted in his Analog Science Fiction review column: "Piper was rapidly becoming the best adventure writer in science fiction before his tragic death..."

H. Beam Piper was a neo-romantic in his approach to his science fiction novels and wrote with the narrative power of Robert Lewis Stevenson and Rudyard Kipling. He was also a great admirer of Rafael Sabatini and his historical romances. As a lifelong student of history, Piper drew much from his study of history, and at the time of his death was working on an historical novel on The Great Captain, Gonzalo de Córdoba. Where Piper differed from many of his contemporaries in the science fiction field was his impressive knowledge of history and his ability to weave it into his narrative. Piper's understanding of history and his cynical view of human nature kept him from the worst excess of romanticism and provided him with a sense of the grand sweep of history not often found in science fiction.

It took twenty-six years of hard work and perseverance before Piper's first story sale, Time and Time Again, on September 25, 1946 to John W. Campbell, the legendary editor of "Astounding Science Fiction." Beam spent his whole life trying to be a writer and when he arrived, he made the most of it. He loved to go to writer's workshops, conclaves, meetings (was a member of both the Mystery Writers of America and the Hydra Club, the SF writers group—precursor to the Science Fiction Writers of America) and especially science fiction conventions.

He was a character, even before his first story sold, but afterwards he 'worked' at being distinctive—even fabricating a life that was fascinating in and of itself. And succeeded, I suspect, beyond his wildest expectations; it's unfortunate that he wasn't around for the Piper revival of the late 1970s and 1980. He would have loved the attention a lot more than Robert Heinlein, who 'appeared' embarrassed by his fame.

Piper's first story made its appearance in the April 1947 issue of "Astounding Science Fiction". John W. Campbell was a well-established author before he turned his hand to editing; he is widely considered the originator of modern Science Fiction and was almost single-handedly responsible for pulling the genera up by the bootstraps and out of the pulp quagmire it had originated in beginning with Hugo Greenback's "Amazing Stories".

John W. Campbell's "competent man" was very similar to Beam's own self-reliant characters, almost to the point where some readers and critics thought Piper was 'pitching' his story ideas to what he thought Campbell would buy, as indicated in his "Astounding" editorials. This was not as far-fetched as it sounds, since several authors, such as Randall Garret, did just that—and made a good living off it, too! Campbell, like Beam, was a man who knew what he liked, said what he thought and believed every word.

In editor John W. Campbell, Beam found a kindred spirit; plus, an editor who highly admired Beam's writing and wrote him detailed letters on how to improve or strengthen—as determined by Campbell, of course—those stories. And, in a few cases, ideas for more stories in "that future history of yours." To Beam, who had wandered in the wilderness of rejection and dismissal for over thirty years, he must have felt like Moses finding the burning bush.

John W. Campbell and H. Beam Piper at the London World SF Convention

John Campbell thought very highly of Beam's work. This June 5, 1962 letter from Campbell says it best:

Dear Mr. Piper

I don't know what plans you have to the next story project, but the world-picture you've been building up in the Sword World stories, or Space Viking stories, or whatever you designate the series offers some lovely possibilities. "Space Viking" itself is, I think, one of the classics-a yarn that will be cited, years hence, as one of the science-fiction classics. It's got solid philosophy for the mature thinker, and bang-bang-chop-'em-up action for the space-pirate fans. As a truly good yarn should have...

Piper's novels are all books of heroic vision, in the vein of Robert Louis Stevenson and Alexander Dumas, that appeal to young adults as well as the young at heart of all ages and can be read and re-read, passed from one generation to the next. Even Ace Books, the present Copyright holder of Piper's oeuvre, policy of benign neglect—having allowed most of the Piper canon to languish out-of-print for the past twenty years—has not stopped readers from searching out Piper's books at used bookstores and on the Internet. Piper's legion of fans gather at obscure web sites and Internet lists to talk about and re-interpret his works and his millennium spanning Terro-Human Future History.

In 2006, most of Piper's short stories and novels fell into the Public Domain and are now available for downloading on-line from Project Gutenberg and from print-on-demand small publishers. We hope to have most of them available from this site on the 'Books' page in the menu.

That a man with H. Beam Piper's talent could die alone, living in hunger and abysmal poverty, is a terrible waste. Of course, like all classic Greek tragedies, this tale has its share of personal hubris, as well. H. Beam Piper was a man of great pride, who enjoyed the fact that his Williamsport neighbors viewed him as a successful author of international renown. Piper was unwilling, despite having several friends living nearby, to tell anyone of his worsening financial situation, desperate enough that he was shooting pigeons from his windowsill for dinner. The idea of going on Relief wasn't open for discussion.

However, when the money arrived for a story sale, Piper did not budget his money well. After a celebratory dinner out, he would go out and buy a tailored suit or two for keeping up appearances. Not really too much to ask for, except that Piper's income even in his best year as a writer was a little over three thousand dollars—just above the poverty level. After his death, his ex-wife Betty wrote: "He was always broke and when he got a check—he blew it—and was broke again."

Piper had his standards; he liked to dress well, even wearing a tie and white shirt while writing alone in the gunroom. Unfortunately, his only controllable expense was his food budget, so when story sales dropped he starved himself, eating condiments at the Busy Bee diner or stale crackers and the remnants in his pantry. Authors in general are not good financial planners; some arrogantly eschew good business practices as being incompatible with art. Others are self-centered and are more interested in their work than in taking care of business. A few just don't deal well with the mundane realities of food, shelter and transportation. As Mike Knerr sums it up best, in one of his letters: "Piper made very little money, but he spent it as though it was Confederate currency."

In his fanzine, 'Paean to Piper,' Dwight Decker gives us this interesting alternative view of Piper's career: "I have a feeling that the tragedy of H. Beam Piper is that he started too late. Ten years earlier and he would have been around for John Campbell's Astounding revolution and the explosion of talent that introduced Heinlein, de Camp, del Rey, Asimov and so many others. If Piper had been in that wave, established a decade sooner, he could have developed into a major figure in his own right and have been far more successful by 1964 and not have felt honor-bound to take his own life."

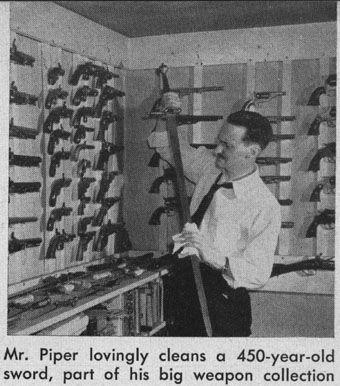

Beam Piper had a love affair with guns that started in school and never ended. Beam had an extensive knowledge of antiquarian arms. In the "Pennsy Magazine," he explains the origin of this interest: "'I was 14, and the Fourth of July was coming up, I wanted to make as much noise as I could for my money, and I decided that percussion caps and powder were better than ordinary blanks, so I got the catalogue of a New York gun dealer and bought a .44 caliber Civil War percussion revolver for $4.85.'

"This not only made a satisfying noise, but started him reading about old weapons, buying them, trading them." This turned into a life-long passion and, as with anything that interested him, Beam quickly became an expert on firearms, especially antiques. He used this knowledge to amass a wonderful collection of antique guns, daggers and swords for rather modest prices.

Beam's friend Mike Knerr gives us a wonderful description of Piper: "Beam continually lurked in lonely silence behind his dark suit and the black overcoat he usually wore slung over his shoulders. Black hair combed straight back, a somewhat pale and aquiline-featured face; he could have been a sort of Bella Lagosi walking the streets of Williamsport, muttering to himself as he plotted another story. He was also inclined to stubbornness, atheism and given the idea of creating an aura of the Victorian about himself most of the time. He often appeared to be a man from the last century, given to wearing white shirts and ties even when he wrote. True to his Victorian code, Beam seldom watched television (except the fights) and never owned one.

"A man of great contrasts, Beam was a skilled craftsman in his chosen field of writing—yet he couldn't produce stories without dozens of drafts on a manuscript. He would seldom "open up" in the presence of women, yet he would often talk freely with men. He was an historian, hunter, gun collector and a disciple of Niccolo Machiavelli, yet he wrote about space travel and science fiction. Being of practical bent (except where money was concerned) Beam wasn't exactly a proponent of space travel, nor the exploration of the galaxy.

"'I tend,' he once said cautiously, 'to put space travel off into the same corner of my mind as I do ghosts, flying saucers and other such things.' When asked about such marvels as the vehicles which transport men to the stars, he grinned: 'Oh, one merely mumbles in their beard about stellar drives and space warps in a convincing manner...and voila!—You're there.'"

The truth was that Piper was very concerned with verisimilitude and went to great lengths verifying facts at the library and with scientist friends. He maintained a detailed correspondence with Jerry Pournelle, then a Senior Scientist at Boeing. After ChiCon, the Chicago 1962 World Science Fiction Convention, on September 3, 1962 Piper writes: "Managed to get in on tail end of lecture by Willy Ley and then a muster of the Hyborean Legion, and lecture by Jerry Pournelle on warfare 1962 - 2000 and political discussion which was adjourned from 1530 to 1730. Out for dinner, very tough shish kabobs. Partying resumed, first in my room and then in Robert Heinlein's. This time I fell out at 0400."

When Sputnik went up, Piper was furious. As Don Coleman remembers: "In early October 1957, Beam was enjoying a 'Katinka' cocktail at Freida Coleman's den bar when a news bulletin broke over TV, announcing the launching of the Russian satellite "Sputnik" that was gloriously circling the earth. It was a severe blow to US technology, learning that the Soviets had fired off an orbiting satellite that would hurl about the globe indefinitely.

"'DAMN!' Beam growled. 'If only Odin had given me a clue. And Thor himself must have surely known!'

"Shaking his head in anger, he continued, 'They got the jump on us. And the DAMN thing is no bigger around than a boxcar wheel; and only a mere 25 pounds heavier than yours truly!'

"He turned to the bar, pulled the ever-existent pad of paper from his breast pocket, and taking his multi-color pen to hand, began to draw 'Sputnik.' Beam utilized the four colors of ink on the small sheet of paper, telling us all the details of how it worked, how it was built and how it was launched. He was so excited because this was something he excelled in! He would sketch what he termed as a 'simple spherical space-oriented vehicular orbiter.'

"Diane Coleman Simpson, who was in Beam's presence this evening...continues:

'Amazing thing happened the next day; the newspaper had a full account of it, including a staff drawing. It was astoundingly similar to the picture Beam had drawn the night before!'

"Far from crude, the likeness by Piper was undeniable in fact, and as sound as his own logic in his conception of space... In less than two months, it burnt up returning to earth, but another had been launched (with dog) just thirty days after the first launching. This irritated Beam further, not only because the United States of America had yet to get a satellite successfully of the pad—but it 'interfered' with his own fictional 'space 'program.'" From that point on, he never again wrote science fiction stories in the near future; instead, they took place centuries or millenniums into the future in his Terro-Human Future History.

In his unpublished biography, "PIPER," Mike Knerr writes: "A craftsman in the field of science fiction, Beam's first love was history (16th Century Italy, in particular) but he found himself part of the science fiction fraternity. Piper truly wanted to write historical novels, but couldn't. As this became more of an obsession, he solved the problem by taking his knowledge of history to the stars, "Space Viking" and "Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen" being prime examples. "Although, Piper never finished his opus in the historical novel field, he continued to plot it and to read history. Writing and writers were his friends and equals on one hand, while guns and gun collectors were his companions on the other."

H. Beam Piper singing program for Barbara Silverberg at London SF WorldCon

"Ventura II," a fanzine published shortly after Pipers death, contains several appreciations of Piper, including SF author Jack Chalker's Lights Go Out: "H. Beam Piper (He never would tell anyone what the "H" stood for) was a talented and imaginative writer who endeared himself to the science fiction world not just by his superb writings, but also by his sparkling wit and personality at various conventions and conferences. He was one of the special group you looked forward to meeting again and again, and who, you know, would be the same cordial gentleman. No one was too big or too small, too famed or too unknown, that he could not talk with Beam as a friend. His pixie-like mannerisms and his twinkling eyes were always at the center of attention. Beam loved people, all kinds of people, and he was never happy unless there was a group nearby discussing history and antique weaponry, and he was often the life of any party.

"He looked somewhat like the classic movie villain, with a thin moustache and a deep, piercing voice—but the twinkle in his eye betrayed his image, and this suited his impish sense of humor.

"It was only in the past few years that he truly matured as a writer, and found his forte in the form of the novel, giving the SF world such masterpieces as "Space Viking" and the novel that truly won him universal acclaim and recognition by all, "Little Fuzzy." His juvenile novels for Putnams, "Four-Day Planet" and "Junkyard Planet," showed him a master of all levels, perhaps the only man who could equal the gifts of Heinlein and Norton in writing juveniles that did not play down, and were often far superior to the bulk of adult fiction. Beam never wrote for adults or for juveniles—he wrote for everyone.

"By 1964 it was very apparent that H. Beam Piper was one of the truly great SF authors, and from the time when he couldn't sell a novel to the magazine or hardback publishers ("Little Fuzzy" was universally rejected) he had, in a few short years, come up to where he would be ranked on the SF five foot shelf with every great writer in the business. In one sense he truly surpassed his contemporaries—his public knew and loved him personally as well.

"In 1964 PhillyCon attendees were rather puzzled when Beam failed to appear for the festivities. He was so much a part of the East Coast's affairs that his very absence was almost physically noticeable. It was then that Sam Moscowitz told us that he had received word that on November 11, 1964, just a few days before, Beam Piper had said his farewell to this world and gone on.

"Beam's thoughts ran deep. He was a very complex man, a very unique and unfathomable man. Behind the villain's façade, beyond even the twinkling eyes and the pixie manner, there were things that showed in no external symptom, and like the ancient ones he studied and loved, he chose his own time and place of farewell, for reasons concealed from us all.

"The news passed like a great snake through the Philadelphia audience.Few would or could believe he was gone. There are those of us who really can't believe it even now. "In a year that saw us lose many great men, for different causes-Hannes Bok, Cleve Cartmill, Mark Clifton, Aldous Huxley, T.H. White, C.S. Lewis, Norbert Weiner, and others -- this loss was saddening indeed. To those that had the pleasure of knowing Beam himself, the loss is doubly felt.

"H. Beam Piper (1904-1964) is gone—but his name will not be forgotten until men cease to imagine far places, new worlds out among the stars..."

Beam, as Jack Chalker mentions, was very protective of his background; in part, because he spent most of his life working as a night watchman at the Altoona, Pennsylvania car yards, writing short stories and novels during his off time. Not a very writer-like career. While an autodidact as well versed in history—maybe more so—than most history professors, Beam may have had some insecurity in regards to his lack of formal education. When asked whether or not he attended college, Piper would reply that he didn't go to college because he had wanted to spare himself "the ridiculous misery of four years in the uncomfortable confines of a raccoon coat."

Mike Knerr has this to say in "PIPER": "Part of the reason for the mystery of Piper lies in his origins. His life was common, his formal education almost non-existent and his knowledge of writing gleaned primarily through a voracious appetite for reading that could never be sated. When he died he was reading, ironically, "Captain Blood Returns." I took it back to the library for him. Early in his life he knew his way around a library and grew up reading the various pulp magazines of the time."

Piper enjoyed the role-playing and mystery involved in 'hiding' his real self. Mike Knerr notes: "Beam wanted to be what he believed a man should be, a living example of what he put on paper and, when he failed in his quest he could not allow it to be seen. The argument with his wife over nothing resulted in a separation that tortured him, yet he felt he could not compromise his decision and, in order to reinforce his attitude, he told lies about it. His bullheaded determination to write un-salable mysteries resulted in wasted time and a lack of funds that eventually had him shooting pigeons to survive. Even in his writing, as skillful as it was, he believed that he couldn't live up to what he felt a writer should be.

"His stories were excellent, almost always earning the Analog bonus of extra money. They were popular with the world of fandom at the time when science fiction was a "closed club," as far as the writing fraternity was concerned. Today, nearly twenty years after his death, his work still ranks among the top ten Analog writers.

"Yet, for all his talent, H. Beam Piper became a man torn apart by the world he lived in and the career he had chosen. His uncompromising, iron-clad outlook cost him the only woman he ever loved and wrapped him in a private despair that never totally left him. Stories were always difficult for him to produce. He wrote draft after draft of a manuscript, fighting to get it together, before he was satisfied with the final product. To him the typewriter wasn't a machine with which to produce novels and short stories, it was a wailing wall of total frustration.

"Piper was generous with his knowledge of science fiction and writing, but extremely chary about his personal life, and he continually lurked in a lonely silence behind a dark suit and the black overcoat he often wore slung over his shoulders. He was recognized by many people, known by very few and understood by even fewer. He was, "that writer...what's his name.

"He was not initially friendly, nor much given to casual relationships with neighbors, but was extremely loyal to those he liked. One was never given friendship by H. Beam Piper; one earned it. "He was opinionated, stubborn and in some ways a bit selfish, and his refusal to bend or compromise what he called his principles often bordered on the absurd. He was an atheist by his own admission, hated Democrats and believed that Social Security was the invention of the devil. He liked animals and often made friends with stray dogs and cats. He was an original. A brilliant, often tormented writer, but an original to the core.

"Little of the character that H. Beam Piper displayed to the world resembled the inner man. Beam preferred to be an enigma wrapped in a riddle and he often went to great lengths to perpetuate this belief...He maintained that attitude toward everyone, a solitary individual who spent his life chuckling at society, politics and the masses and the clumsy handling of their affairs.

"A Machiavellian philosophy permeated most of his writing and his general attitude toward the world, yet this was only one facet of his character and was frequently over-ridden by a genuine compassion that could surface within him.

"His life, and the various myths that swirled around him, is difficult to bring into focus as the character of the man himself. Swathed in secrecy and a verbal smoke screen of self-produced fiction, he lived out his final years in a lonely, frustrated existence that few people, if any, understood. Except when it suited his purposes, he refused to discuss his past and his origins and, when he did, he frequently lied. He generally summed up everything with a favorite expression: 'Man is born, he suffers, he dies; so far, I've done two thirds of this.'"

There are skeptics who believed that Piper's suicide was a cover-up for murder; a murder that echoed Piper's own locked-room mystery, "Murder In The Gunroom," too closely it was said to be mere coincidence. In "Murder In The Gunroom" Lane Fleming, a noted collector of early pistols and revolvers (modeled after Piper's friend and mentor Colonel Henry W. Shoemaker, who had a valuable gun collection Piper catalogued in 1927, and to whom his mystery was dedicated) was found dead on the floor of his locked gunroom with a Confederate-made .36-caliber revolver in his hand. That suicide was made to look like "death by accident" until Piper's detective Jefferson Davis Rand proved otherwise.

With the wealth of information I have unearthed over the past thirty years, I intend to lift this veil of secrecy from Piper's life and show my readers the real H. Beam Piper beneath his carefully created facade. Over ninety-percent of information that appears in the forthcoming biography "H. Beam Piper: A Biography" has never been published, nor made available through the Internet or any other source. This is the first H. Beam Piper biography. It will reveal "the man" inside the black cape; the animal lover, the friend of children everywhere, the lonely man who was imprisoned by his own solitude and unaware of the high regard he was held in by his peers and the science fiction readership—all of whom were stunned by his unexpected suicide.

John F. Carr