|

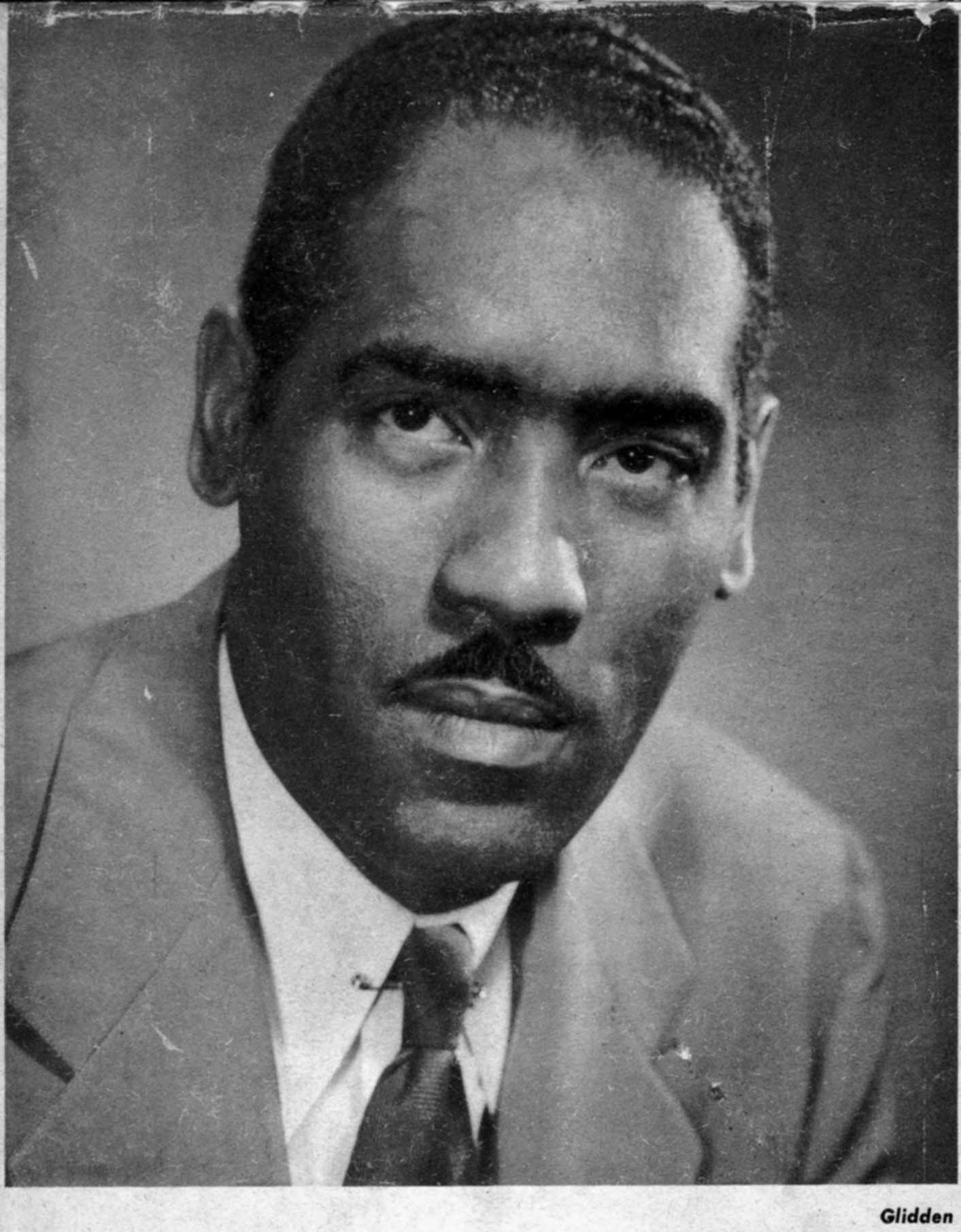

"My Talk with

Talmadge"

By Roi Ottley

|

"How does it feel to be a Negro?" is a

question I am frequently asked by white people. Nearly 100,000 books,

pamphlets and tracts have been written about the Negro and countless studies and

investigations have been made. Yet, no one seems to have the answer.

Perhaps I can illustrate one aspect of "being a Negro" with an

incident from my own experience.

I have always resisted the slogan, "See America

First" - especially when the appeal suggested traveling in certain sections of

Dixie. However, in connection with a newspaper assignment, I made a trip

to Georgia to interview Governor Herman Talmadge. I was made indelibly

aware of the fact and feeling of being a Negro - a thing often naked of dignity

- from the moment I arrived at the state capitol in Atlanta to keep a scheduled

9 o'clock appointment with the governor. This innocent mission churned so

much emotion that my feelings were mangled in the process.

The day was bright and sunny. The stately building,

surrounded by neatly-manicured lawns and hedges, had an air of mellowed

culture. I paused a moment to watch a bent old Negro slowly clip the

hedges. I had seen him before; the man with the hoe, done in black. |

Georgia Governor Herman E. Talmadge (Served from

1948-1955) |

The atmosphere inside the capitol's shabby paneled corridors,

had the air of a political clubhouse. The place swarmed with a motley

group of white people. This morning they had one thing in common - a

disagreeable incredulity at seeing a Negro in the capitol. Consequently, I

picked my way deftly through the crowd, careful not to jostle anyone and give

cause for open hostility. The fact was that those around me could not

throw off their dehumanized image of the Negro - an image challenged by my

conventional appearance. Thus, I was forced to assume an air of elaborate

politeness in order not to give offense. To be sure, I hated myself for

donning the cloak of Uncle Tom. But I reasoned my assignment was more

important than my personal feelings.

The first person I approached was the receptionist - a gray

haired, stylishly dressed woman who might have been the prissy mistress of a

fashionable girls' school. When she spied me heading towards her, she

flushed deeply. Suddenly, she began to noisily shuffle papers, pretending

to be extremely busy.

I knew I would have difficulty unless I handled the lady

gingerly. Seemingly, she was the type who had learned well the black

business of "keeping Negroes in their place." So I stood before

her desk and waited for her to ask my business. She ignored my presence

and sought, instead, to interview anyone within shouting distance. When

she could no longer recruit people and thus have a pretext for passing me up,

the lady coldly asked what I wanted.

This gentle lady never lifted her eyes while making the

inquiry. The procedure was painfully distasteful to her. She made no

attempt to conceal her feelings. Her manner placed me in the position of

an intruder, a black alien. Her haughty agitation inspired the white men

about her to crowd around her desk protectively. They made it clear that

the regarded me as a dangerous character - or, at the very least, a bumptious

messenger who, somehow, had wandered through the wrong door of a country club.

Even the white-coated Negro porters, equally surprised by my

appearance in Georgia's capitol, paused in their chores and nervously watched to

see what would happen. I was completely isolated now. Silence fell

upon the corridor, almost with a thud. Everyone listened attentively to

hear what I was about to say. For a brief moment I had to summon my

voice. But I experienced a perverse pleasure in boldly announcing: "I have a nine o'clock appointment to interview Governor

Talmadge."

I suppose my voice carried a note of triumph. I had

tried to modulate it otherwise. But my manner betrayed me. I could

not genuflect to the rigid decorum a southern white woman tries to exact of

every Negro male in public. The compulsion to assert myself, however small

the gesture, compelled me to toss off the shattering news.

One would suppose I asked the lady for the next dance.

Her freckled hands trembled and perspiration dewed her forehead. I thought

she might faint. She paled and appeared almost speechless. Someone

had neglected to tell her before hand about the Negro who was scheduled to see

the Governor. There was a stubborn disbelief in the eyes of the crowd as

well.

With this subtle support, the lady primly recovered her

composure. "And what do you want to talk to the Governor about?"

she asked.

As politely as I could, with my resentments mounting, I

explained that my business was for the Governor's ears only. She

instructed me to leave the building and return in one hour - this apparently to

avoid inviting me to be seated. No one believed my fantastic story.

But when I hesitated about leaving, I apparently hung everyone on the horns of

dilemma; the men who eyed me as if I had said something offensive, pondered what

next to do; the receptionist, who perhaps felt I was deliberately difficult,

undoubtedly had visions of announcing me and being noisily reprimanded for

unpardonable ignorance; the Negro porters, who had perhaps regarded me as an

upstart northern Negro, seemed worried that I might stir the white folks to

anger.

The wall against me was solid. I felt routed as I

left. Nevertheless, I returned in an hour, I was met by cold, blue,

brittle stares. I felt chilled to the marrow. The faces formed a

grim gauntlet as I strode directly to the receptionist desk. This time,

with my patience ebbing, I insisted upon being announced. But the

receptionist's defenses had been thrown up; in a preparation for my return she

had called the guards. They edged close, alert to seize me if I made a

move faintly aggressive.

I wondered vaguely what my course should be in case of untoward incident - fight

or flight! The woman herself was in an equal quandary - and because of

this, she eyed me with a sullenness I felt might explode. But with a

let's-settle-this-now attitude, one of the guard's urged her to check my

story.

Finally she picked up the telephone receiver. She

wheeled in her swivel chair and gave me the back of her neck. I could not

hear what she was saying, but utter disbelief rang from the other end of the

wire. The woman became red to the roots of her hair when she put down the

receiver. He eyes blazed angrily. The dilemma was not mine.

But before I could consider what to do next, a handsome young woman opened a

nearby door marked "private," and poked her blond head out and sneaked

a peak at me. She withdrew quickly and perhaps dismayed by what she had

seen. I was the cynosure of all eyes, as everyone waited my next

remarks.

The place became a vortex of racial tensions. And I

suddenly became wet with perspiration - what if the governor had forgotten the

scheduled appointment! But suddenly the telephone buzzed. The

receptionist answered eagerly perhaps anticipating a throw-him-out order.

The crowd seemed to strain forward hopefully. But from

a confident, full bosomed manner, her body suddenly sagged. She listened

with widening eyes, asked for confirmation repeatedly, and finally in amazement

turned in my direction. "The Governor will see you now," she

announced, shrugging helplessly at the disappointed crowd.

There was a marked contrast between the behavior of this

female go-between and the chief executive of Georgia. To begin with, he is

educated and well traveled. He conducted himself with eminent civility and

observed all the social amenities expected of a gentleman. His behavior,

though not chesterfieldian, was in marked contrast to that of his subordinates,

who were openly disturbed by his tradition-shattering invitation to a

Negro.

As I was ushered into his small private office, Talmadge rose

at his spacious desk, greeted me cordially, offered me a long cigar and

comfortable chair, and inquired how I was enjoying Atlanta. He was relaxed

and informal. When he had completed the amenities, he sat down and threw

his big feet on the desk. He eyed me carefully, though not with hostility.

He drew heavily on his cigar, leaned back in a cloud of smoke, and waited my

first question. His manner was superbly confident, even

affable.

To be sure, all this happened behind close doors. But

two bulky agitated gentlemen, who measured me suspiciously, sat in on the

interview. The Governor did not offer to introduce them. I was

afterwards assured they were not bodyguards, as I had presumed. Maybe the

governor only wanted some precinct "boys" to sit in to hear what the

Negroes are talking about these days; or, maybe he had them in as witnesses to

the fact that the chief never allowed a Negro any social

liberties. In any case, to judge by their stolid expressions, what

transpired either bored them utterly or passed over their heads entirely.

I had sought this interview with Herman Talmadge to

discover, even perhaps evaluate, what sort of demagogic personality ran

Georgia's political machine that caused so much grief to the

Negro. The first question I put to him concerned freedom of the

ballot. He answered with the old chestnut - by conceding the

Negro's right to vote, but viewing with alarm "Negro bloc

voting" as a danger to the South. He illustrated his

contention with a referendum held in Georgia's Wayne County, in which a

solid Negro vote defeated prohibition.

This development he described as a "miscarriage

of justice" and complained that the wishes of the white

community had been thwarted, as indeed it was in this case. He

refused to acknowledge this as the working of the democratic

process. His view, he made plain, was that the will of the people

should prevail always, even indeed when it happens to be minority

opinion. Afterwards, I learned, he used this incident to propagandize

against Negroes exercising the franchise.

The young executive bemoaned the fact, in further laboring his

"bloc vote " theme, that "northern prejudice prevented

Southerners from aspiring to the presidency of the U.S. - an observation

that might suggest his ultimate ambition. In any case, he declared

accusingly, "You Negroes in Chicago, New York, Detroit,

Philadelphia, and Cleveland vote against all Southerners, no matter who

they are." The power of the Negro ballot in the North which

Talmadge acknowledged by implication, had alarming meanings to

him. He made it clear the pattern would not be repeated in Georgia

- that is, if he had his way!

Fear of mob violence and police brutality hangs

heavily over the Negro in Georgia, particularly in rural Georgia.

Therefore, security of person, I told the governor, was the Negro's most

urgent need today - "So Negroes don't always have to peek through

the windows, before opening the door," was the way I phrased the

feeling current among Negroes. He flatly denied knowledge of such

fear among Negroes and cited three separate occasions when he had

furnished state police to protect the lives of Negroes. "If Negroes

really fear for their lives," he said somewhat plaintively,

"nobody told me about this."

Even so, he declared, Negroes were better off in the

South than in the North. "Why, the Negro race in the U.S. has

made greater progress during the last half century than any other of the

world's backward races," he declared. He pointed to the existence

of prosperous Negro doctors, lawyers, bankers and businessmen, and to

outstanding Negro universities in Atlanta - which incidentally are

maintained not by Georgia funds, but by Northern philanthropy.

Talmadge ascribed Negro progress to the policy of segregation in the

South.

I replied that segregation - the theory of

"separate but equal" - was a demonstrated failure

everywhere in the country. Talmadge only shrugged in answer to

this remark, and offered no rebuttal, though his silent spectators

blinked curiously. But he afterwards amended his theory of Negro

progress to say Negroes were economically better off in the South, and

indeed had always been.

Governor Talmadge is hardly as crude a racialist as

Negroes believe. He urbanly {sic} used the term "Negroes"

or "colored people, " not the offensive "niggers" or

"nigras." However, I came away convinced that beyond

these delicate shadings of speech, there is no difference in his basic

racial philosophy and that of his followers. Actually, they only

differ in techniques. Both have identical aims: to keep the Negro

a second class citizen.

The above article appeared in Bronzeville Magazine, November

1954? The St. Bonaventure

University Archives owns the original type-script for this

article.

|

Last updated:

05 December 2011

|