The Life of Therese Bonney

Therese Bonney was born Mabel Therese

Bonney in Syracuse, New York on July 15, 1894, the daughter of Anthony Le Roy and

Addie Bonney. At the age of five Therese moved with her mother to California

and remained there until her graduation from the University of California at

Berkley. It was at this point in her life that she stopped using her first

name and began going by Therese. A year after her graduation she went to Harvard and got her

MA

in Romance Languages. She then went to Columbia university to prepare for her

Ph.D. She finished her education in

Paris where she was the first American to receive a scholarship to attend the

Sorbonne. She received the degree of Docteur des Lettres degree there in

1921 after passing her exam with the highest honors. After

her graduation she was awarded multiple scholastic honors, including the Horatio

Stebbins Scholarship, The Belknap, Baudrillart, Billy Fellowships, and the Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation Oberländer grant in 1936 in

order to study Germany's contributions to the history of

photography.

After her education she spent

much of her life abroad with Paris as her "headquarters" (Robertson). Even though she had initially wanted to be an

academic, her experiences in Europe caused her to change her

plans. It was now her goal to help develop cultural relations between the

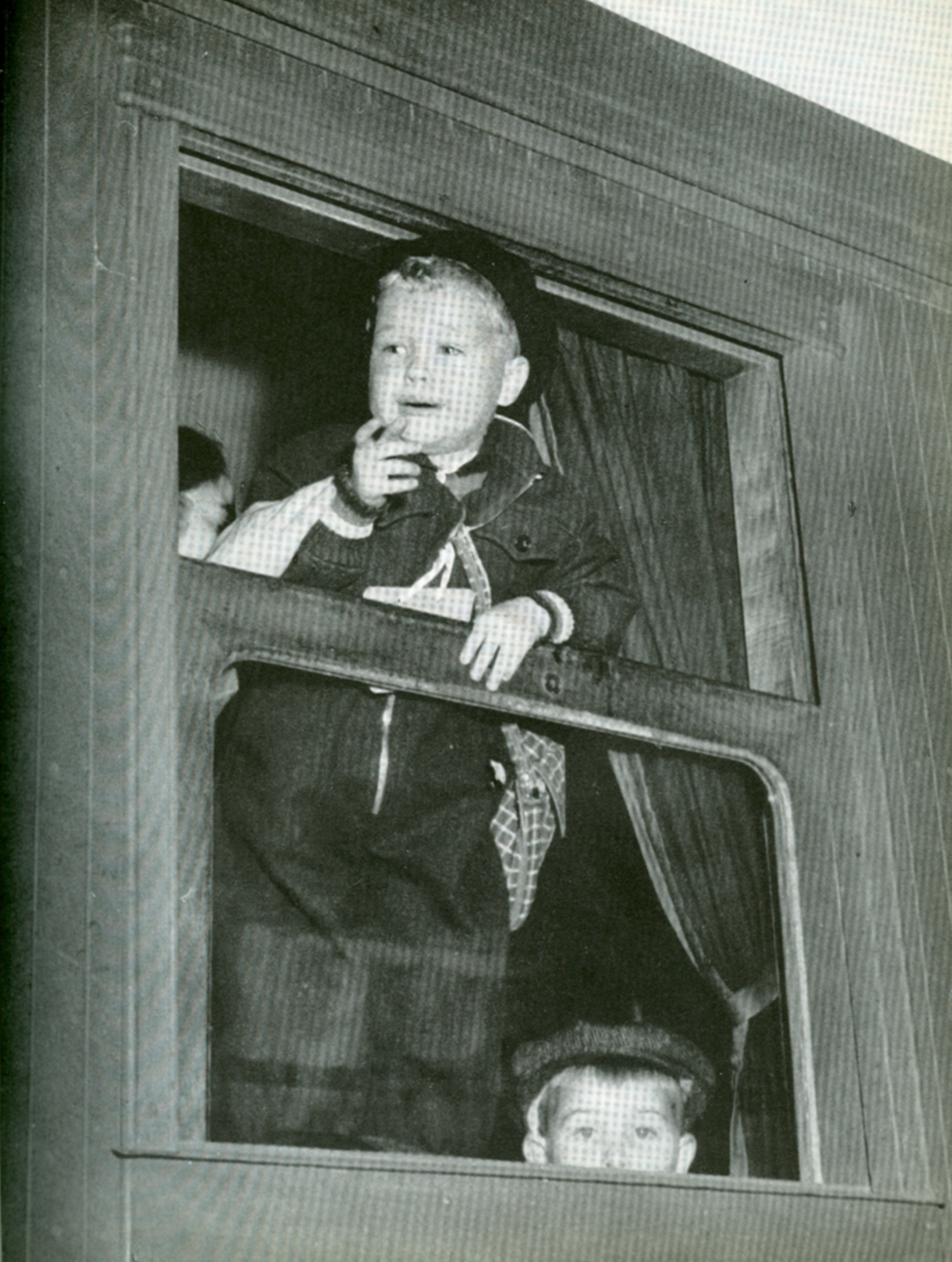

United States and France. In the years following her graduate studies she

helped to establish the Red Cross' correspondence exchange between the children

of Europe and the children of the United States. She also traveled

throughout all of

Europe lecturing and helping to organize Junior Red Cross groups in other

countries. It was during this time that Bonney became interested in

journalism and the power of the media. She had assimilated herself into French society and set up her headquarters in Paris and soon became a

frequent contributor to newspapers and periodicals in England, France, and the

United States. Soon after, she founded the first American illustrated press

service in Europe known as the Bonney service.

Bonney was also a sought after

model. She was "acclaimed as the most perfect da Vinci model in the

world." (Syracuse Herald) She modeled for artists in

France and Spain.

In 1929 Therese Bonney added

writing books to her list of accomplishments when Robert M. McBride and Company published a series of guide books

which she prepared in collaboration with her sister Louise Bonney. These books

included such titles as Buying Antique and Modern Furniture in Paris, A

Shopping Guide to Paris, Guide to the Restaurants of Paris, and French Cooking

for American Kitchens.

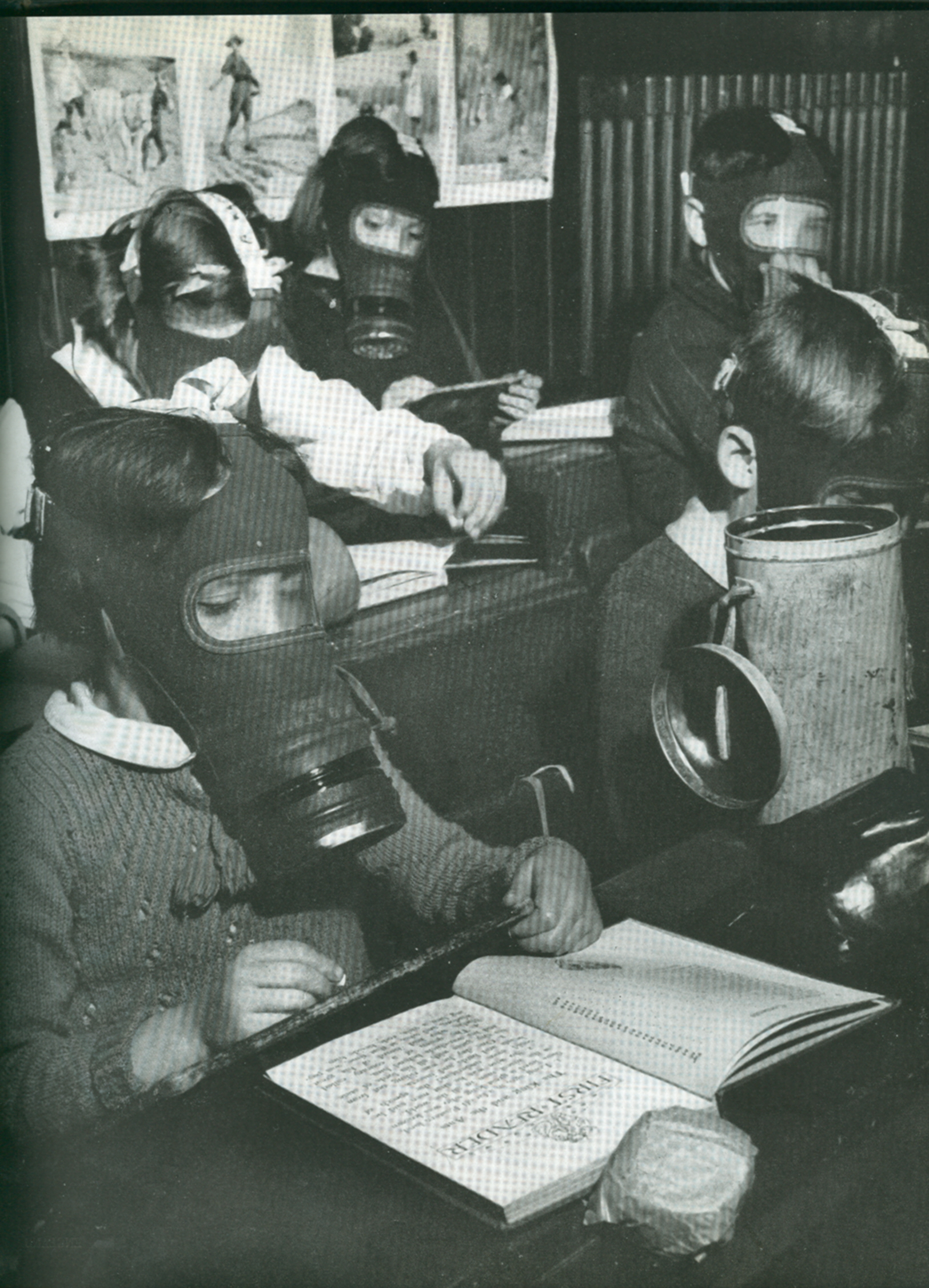

Though she lived much of her

life in Paris, Bonney never considered herself an ex-patriate. Rather, as

she noted in 1978, "I have made my headquarters in France since 1918...I am

the dean of the American press corps in Paris. Nobody outdates me."

(Robertson)

In Therese Bonney's old age

she was still interested in helping

others. She now set out to reveal the plight of the elderly around the

world, and wanted to compose a book on the elderly, in the same style she

made Europe's Children. She took up efforts to extend Medicare to elderly Americans over

seas and worked to raise awareness of the elderly around the world. At the age of 80 Bonney

was presented with a second Doctorate in gerontology at the Sorbonne. Unfortunately

she died soon after at the age of 83 on January 23, 1978 in an American hospital

in Paris.

References